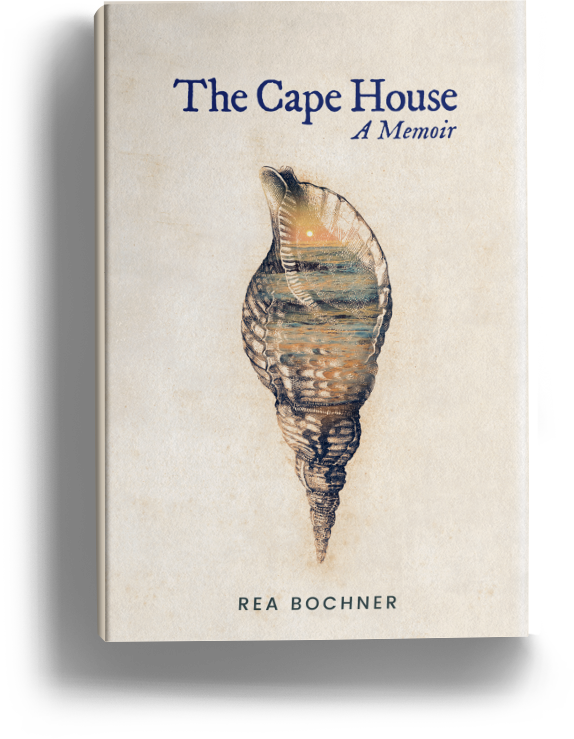

Last week, my family went up to the Cape House to help my father clean everything out. Barring any complications, the sale will close in one week, and the house will officially belong to a new family.

I chose not to go there with everyone. I had my reasons, both practical and emotional, for staying home, and I believe it was the right decision. But I was foolish to think that I could beat the loss with geographical distance. Over the past few days, the loss of the Cape House has hit me with the force of a head-on collision. It was the last physical tie I had to my mother and to the family life I once had there. It was the “Home” setting on my spiritual GPS, the one place in the world I could rely on as a safe refuge. Without it, I am untethered.

My friend Laura says that “grief is love with nowhere to go.” It’s one of the saddest and most true things I’ve ever heard. One the shittiest parts about grief is that no one can do it for you. You have to walk through that dark forest all by yourself. Knowing that other people are lost in there, too, doesn’t always help; their path may run parallel to yours, but it never intersects. Which is why, at moments, grief is a terribly lonely place.

I was talking about all this with my husband the other night, which led him to make an interesting comment. “I don’t like the expression, ‘a blessing in disguise.’ It’s not disguised. The bad stuff is a blessing, too, because it’s part of the good stuff.”

“Example, please.”

“Like your mom, right? It sucks that she died. But it hurts so much because you had an amazing mom. The loss is connected to that. I think it shortchanges the bad things to call them disguised blessings. They’re just blessings.”

It reminded me of a something my friend Penny told me once. When she learned her husband had died in a motorcycle accident, the first words out of her mouth were, “Thank You, God.” She wasn’t an abused wife or the recipient of some life-altering insurance payoff. It was a devastating loss for her, and she was heartbroken. But she also knew that everything was a blessing – and not just because it might lead to good someday. The fact that she was alive and able to experience the loss, the fact that she’d had a husband she loved so deeply, the fact that she trusted in a God she knew would carry her through it, all of these things were a blessing.

This is black-belt spirituality, my friends. I am so not at that level. I’m not even sure I have a belt. I might just be the guy who sweeps the dojo after class.

That said, I have been ruminating on these conversations and holding them up against my losses. Is the loss of my mother really a blessing? Of the baby I miscarried this summer? Of the place I called home for half my life?

I believe the answer is yes.

But to get there, it requires a subtle shift in perspective, like a giant mirror held up to a sunset. The reflection is equally beautiful; it’s just flipped. Until recently, my view of blessings fell in line with the Merriam-Webster definition: “things conducive to happiness or welfare”. This meant anything that worked out in my favor, that benefitted me, or that felt good to have. But the truth is, some blessings hurt. Some blessings, like when I started working full-time, are overwhelming. And some can change your entire life – even when you liked it just fine before. All of these blessings are conducive to happiness or welfare as they’re happening, because we are alive to receive them. They rip us open like gifts.

The blessings I received this summer have broken my heart. But as I learned from some wise people, “When someone gives you a gift, shut up and say thank you.” So I am.

I will also say thank you for Dr. Victor Frankl and his book, “Man’s Search For Meaning,” which has appeared in my life with supernatural timing. Frankl was a Holocaust survivor and psychotherapist whose movement, “logotherapy,” was based on the belief that man’s most powerful motivating force is finding a meaning in life. I’ll leave you with a story of his that I read just this morning and hit just the right notes to ease my heart:

Once, an elderly general practitioner consulted me because of his severe depression. He could not overcome the loss of his wife who had died two years before and whom he had loved above all else. Now, how could I help him? What should I tell him? Well, I refrained from telling him anything but instead confronted him with the question, “What would have happened, Doctor, if you had died first, and your wife would have had to survive you?” “Oh,” he said, “for her this would have been terrible; how she would have suffered!” Whereupon I replied, “You see, Doctor, such suffering has been spared her, and it was you who spared her this suffering – to be sure, at the price that now you have to survive and mourn her.” He said no word but shook my hand and calmly left my office.

In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning.