Many people assume, since my mother passed away at The Cape House, that it’s a painful place for me to visit. They ask, gingerly, “Have you been back since she died?”

“Of course,” I reply with a smile. “It’s my most favorite place in the world.”

What they may not understand is that, while my mother’s death is a pivotal event that took place at The Cape House, it is only one of many memories this place contains. A year after my mom died, my second child was born in the living room, with Mom’s portrait looking over my shoulder. In this house, there have been countless family dinners, holidays, and Fourth of July barbecues, late-night talks, good, long cries, loaded arguments, movie marathons, and storms of laughter that thundered off the high ceilings. Walking into this house, as the garage door hums closed behind me, I am awash in 20 years of memories – with my old journals in the closet to prove it. In the basement are relics of my family’s history, from old school projects to ancient photos to yellowing love letters my mother wrote to my father during an interminable class in high school. So, yes, there are many painful memories associated with this house, but they are but a few in a wild jumble of memories that comprise my life.

Which is why it’s taken time to swallow the news my father gave me a few days ago: he’s selling The Cape House.

Objectively, it’s a smart decision. His life is moving in a different direction than it was when he bought this place. My siblings and I are scattered across the country, and, busy with our own families, are coming less and less. Mom, the magnetic force that pulled us all together, is gone. The time has come.

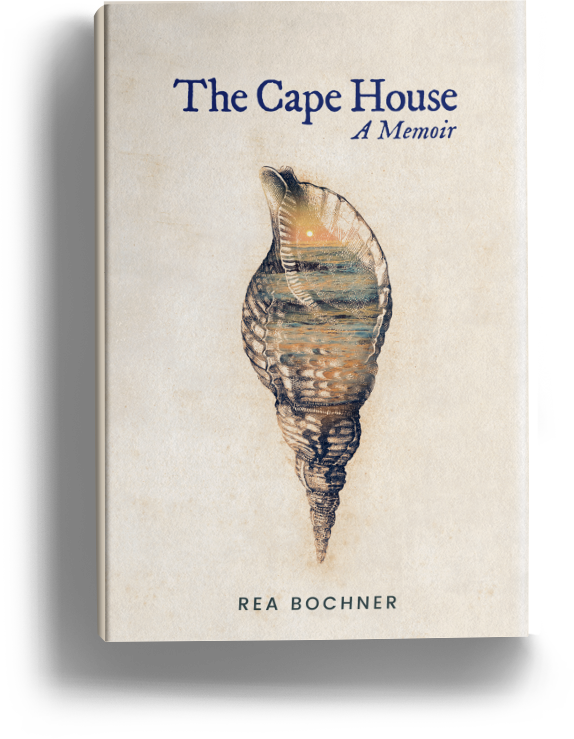

But that doesn’t mean I like it. I have a marrow-deep attachment to The Cape House and everything it represents. I mean, I wrote a BOOK about it. The idea that it might not be in my life anymore, might not be in my children’s lives, stirs a deep, melancholy longing I’ve learned to identify as grief.

But I’ve lived with grief for a long time – I’m something of a professional at this point – and while I know what’s coming, I’m not there yet. For now, I can drink in the time we have left here, watching my sons play in low tide, draping across the couches with the throw pillows my mother made, playing foosball in the basement, leafing through old photo albums (including the one from my bat-mitzvah that I forbid outsiders to see), lounging with a book in the sun, breathing in the salt-rich air, and feeling that everything-is-well-and-peaceful feeling that this place inspires. And I can feel the gratitude for what The Cape House has been for me, alongside the heaviness of knowing I will have to say goodbye to it soon enough.

It reminds of the weeks before my mom died, drinking in every moment, every breath, every flicker of her eyes, all the while feeling time passing with a slippery finality. I played John Mayer’s “Stop This Train” over and over, hearing his smoky voice put my feelings to words:

“Once in a while, when it’s good, it’ll feel like it should, and they’re all still around, and you’re still safe and sound, and you don’t miss a thing ’till you cry when you’re driving away in the dark, singing, ‘Stop this train, I want to get off and go home again, I can’t take the speed it’s moving in, I know I can’t, ’cause honestly, won’t someone stop this train?'”

It’s the same feeling I have watching my children grow up, evolving with sneaky speed from wrinkly little raisins to angel-faced toddlers to wild boys who wipe off my kisses. Even my baby, who just a blink ago was a fuzzy-haired bean wrapped in a sling at my chest, now assures me he is a “big boy who watched Toy Story 3 100 times.”

There is no stopping the train of time. I’m as powerless against it as if I tried to still a real locomotive with my hands. I both hate and am humbled by this. Life is a series of hellos and goodbyes, of embraces and letting gos, of arrivals and departures. While it’s true we can’t take what we love with us, our loves also never leave us completely. They imprint themselves on our memories, in our blood, on our very souls. Even when they are lost forever, they’re never fully gone – they become a part of who we are.

Now to remember this the day the sale goes through.